An introduction to the “Hard Roads to Shu”, their environment, history, and adventures since ancient times

David Jupp[1]

URL: http://www.qinshuroads.org/

Originally written 2010; Last Revised April 2015.

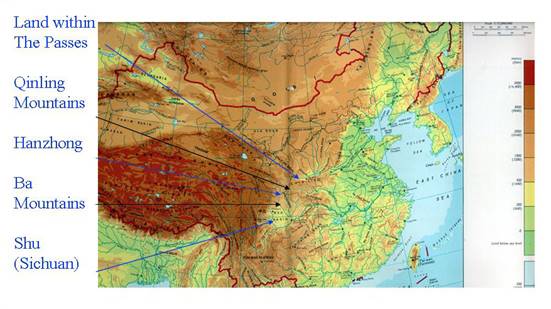

Since ancient times, Chinese people have moved between the Guanzhong or “land within the passes” in Shaanxi, where the ancient capital now called Xi’an stood, to the plains of Sichuan or ancient Shu. The Qinling and Daba Mountains form a formidable barrier to communications but by skilfully navigating the terrain and developing innovative technology called “Plank Roads”, ancient people created effective trade and traffic routes between the north and south. These communication lines are collectively known as the “Shu Roads” or more poetically as “The Roads to Shu”. They pass through rugged mountains, forests, wild rivers and natural wilderness, containing conservation areas, ancient historical relics and the homes of minority peoples whose isolation has developed diverse cultures. The roads provided a bridge between southern trade routes such as the Tea and Horse road to Tibet and northern routes such as the Silk Road to the west and form part of the “Great Road” from Beijing to Yunnan described by Marco Polo. They are well known in the cultural traditions of Chinese people but are not as well known in the west. As the history and ecology of these areas become better known, a well defined “Shu roads ecological and historical tourism route” has developed where historical, ecological and adventure tourism will expand in the future and become better known outside China as more international travellers and tourists visit.

Introduction

The name “Shu Roads” is a general term applying to the historical roads that were built through the mountainous East-West barrier formed by the Qinling, Micang and Daba mountain ranges [W.1]. The Shu Roads linked the Wei river valley (or the Guanzhong) with its cluster of ancient capitals, such as Chang’an, near present day Xi’an in the north and the Sichuan plain with its ancient capital at Shu (present day Chengdu) in the south. They pass through some of China’s roughest and most inhospitable terrain. The first of the major highways was most likely built in the Warring States (481-221 BCE) period with extensive and advanced road building occurring during the Qin (221-206 BCE) and Han (206 BCE to 220 CE) dynasties. In most cases they made use of natural corridors that had been discovered and used much earlier by ancient people. Some of the routes have been maintained and consolidated up to modern times while others have faded from view. The establishment of these important traffic routes through difficult, steep and dangerous mountain ranges required the development of innovative road building technology known as “Plank Roads” (Figure 1) by which ravines and steep sided gorges were traversed using trestles fixed into the rock face. [2]

The Tang poet Li Bai (701-762 CE) travelled these roads to exile as did many of his friends. He wrote “The Road to Shu is hard, harder than climbing to heaven” and described the Plank Roads as the “ladders to heaven”. But armies, traders, settlers and materials also flowed through these roads for more than 3000 years during which time the developments associated with the Plank Road technology, and the turbulent history associated with the Shu Roads, have together become part of China’s historical and modern culture.

|

|

|

Figure 1: Reconstructed Plank Road at Mingyue Gorge in Northern Sichuan |

Between the northern and southern sections of the Qinling and Daba mountain ranges is the Hanzhong basin through which the Han River flows to meet the Yangtze River at Wuhan in Hubei. The course of the Han River has provided an East-West corridor to the Hanzhong Basin and Hanzhong has provided a welcome staging point between Guanzhong and Shu since ancient times where an active shipping trade also provided welcome relief from portage. The strategic importance of the rich and productive land and environment of Hanzhong is well known in history but apparently forgotten in the relative anonymity of Hanzhong (even in China) in past years. But interest in the history and archaeology of the Hanzhong Basin has increased in recent times. Playing a key role in this awareness, the Museum at Hanzhong is preserving and making known the rich heritage of the region including the cultural and historical aspects of its ancient Plank Roads and increasingly Chinese people are coming for educational, historical and adventure tourism to the place where the Han dynasty originated.

|

|

|

Figure 2: The three “lands within the passes” of Guanzhong (the Wei River Valley), Hanzhong (the Han Valley) and Shu (the Sichuan Plain). |

In recent years, the author of this introduction and others have undertaken a project to make use of modern technologies such as Remote Sensing, GIS and GPS to help map aspects of the Shu roads (see the Qinling Plank Roads to Shu web site at [W.2]). The project investigated the role of technologies that could help the Museum and others to document, manage, preserve and conserve the geographically scattered relics as well as communicate geographical and terrain aspects of its history to scholars and visitors alike. Such activity is a step towards a “digital museum” of a kind more common in other countries and other parts of China than previously in the west of China. For more information about this effort you are welcome to visit the web site at [W.2].

The Geography and Geology of the Qinling and the Shu Roads

Geography

The Qinling and Daba Mountains are part of a central mountain area of China running east-west from the Kunlun range in the Qinghai-Tibet plateau and reaching almost to the sea near the Huai River of the North China plain (see Figure 2). This mountain range, which reaches its highest point at 3750m on Taibai Mountain, is a barrier creating differences in China’s environment, climate, natural resources, history and culture between the north and south. The system forms a distinct, but permeable, historical frontier region between north and south in the sense described in a paper by Mostern and Meeks [R.8]. In this region, communication, traffic, trade and migrations between north and south have played as great a role in its history as has its terrain. Together they developed as a natural “great wall” that both isolated and protected the western regions.

The differences are especially clear between the three protected basins in the west of China that were linked by the Shu Roads. The most northerly of these is within the watershed of the Wei River and its tributaries in Shaanxi. The waters of these rivers join the Yellow River to reach the sea in Shandong. This area has been known for a long time as the Guanzhong, or the “the Land within the Passes”, and is a site of prehistoric Chinese civilisation since the Stone Age and the site of the earliest agriculture. It is where the Western Zhou (1100-771 BCE), Qin, Han, Sui (581-618 CE) and Tang (618-907 CE) as well as many originally foreign northern Dynasties grew and emerged to conquer and govern parts, if not all, of China. Chang’an (present day Xi’an) is a city which has been the centre of government for China for the longest period of its history. The Guanzhong takes its name from five major (and other minor) barrier passes through the mountains that form the “gates” to the area through the mountain barriers and provided natural sites for its fortification.

Although the Guanzhong is best known, there are two other “lands within the passes” to its south (see Figure 2). To the far south, across the Qinling and Daba Mountain ranges lies the Sichuan basin. Although its archaeology is not as widely known as that of the Guanzhong, the Sichuan plain has also been the site of ancient civilisations which grew in parallel with those of the north and east. Sichuan has been a populous, rich and fertile area for thousands of years and has mostly (with some notable exceptions) been able to avoid the turmoil of the east of China through its natural protection by high mountains and steep gorges. However, it was also the natural resources of Sichuan that brought armies and settlers from the state of Qin across the Qinling from the Guanzhong in the Warring States period, building mountain roads to conquer Shu and develop agricultural production using advanced irrigation engineering.

Finally, in a central position between the other two areas, south of the high Qinling Mountains and north of the Daba and Micang mountains lies the Hanzhong basin. The mountain ranges separate the drier, predominantly wheat growing areas in the north from the wetter, predominantly rice growing areas in the south. The climate and agriculture as well as the wildlife and natural vegetation in Hanzhong are transitional between north and south. The Hanzhong basin was known in ancient times as “Yu Pen” or the “Jade Basin” for its rich natural resources and productive soil and this together with the shielding high mountains and rapid-filled rivers have made it a place of refuge for many in times of turmoil. These characteristics, together with its central location have also made it the linking region for the traffic between north and south. Its central role grew in importance as people found ways to move across the mountains between the Guanzhong and Shu and ways to move along the Han and other rivers to link Shu, Guanzhong and the lower Yangtze River area. The roads they built between north and south were the Shu Roads (Herold Wiens [R.1], [R.2] & [W.3]; Chinese readers see Li Zhiqin [R.6] and Feng Suiping [R.7]).

|

|

|

Figure 3 The rugged Qinling mountains are wilderness areas of great beauty. |

Geology

Geologically, it is thought (Meng and Zhang, [R.9]) that the north and south sections of the Qinling (Daba being regarded as part of the south section of the Qinling) were formed in geologically recent times (late Triassic to Paleozoic) from collisions between the north and south China blocks. The extensive east-west striking folding, faulting and mountain building resulted in a change in climates between north and south China leading to north China drying, to Loess formation and to the separation of the present Yangtse and Yellow river basins. The subsequent cutting of river valleys both along and across the main east-west structure has formed a characteristic geomorphology of deep valleys separated by granite and sandstone ridges. The sediments cut from the mountains filled valleys and small basins – such as Hanzhong. Although the tectonics of the south Qinling are different from those of the north, the mountains are also inhospitable with sharp peaks separating steep ravines and fast flowing rivers. At the western edge of the Sichuan Basin lies the north-south striking Longmen Mountains where the Qinghai-Tibet block meets the south China block. The three blocks collide at the three-way border region between Sichuan, Shaanxi and Gansu. The mountains and blocks are still tectonically active as was tragically illustrated recently when the Longmen Fault slipped to bring about the destruction of the May 2008 Wenchuan earthquake.

Geomorphology

Obviously, a significant flow of goods, people and communications within, through and across a divide with rugged landscapes like those in Figure 3 could be difficult to achieve. However, the permeability of a barrier does not depend on how steep are the hill slopes but rather on whether there exist connected paths through the system and whether people can learn to navigate the terrain as well as (for example) mariners have learned to cross equally formidable oceans to trade and interact. In the Qinling, the people of ancient times certainly found pathways from the north to the south and vice versa. Papers presented at the Hanzhong Symposium in 2007 provided evidence of extensive communication since Paleolithic and Neolithic (prior to 2000 BCE) times and during the Shang and Zhou (prior to 1000 BCE) periods. The means by which ancient people travelled to Shu from the rest of China must generally have been via the rivers and valleys since the ridges were and are generally very steep and sharp. This meant using boats where possible along stretches of major rivers (as was described in relation to the Han River by other papers at the Symposium) and also using the valleys cut by rivers to access the mountains. But the rivers are confined to watersheds and to cross the watershed divides it is also necessary to find and use saddle points of the terrain so that the pathways within the watersheds can be linked and become Shu Roads. As Herold Wiens [R.1], [R.2] & [W.3] pointed out, the significant terrain points at watershed divides make up many of the “gates” or “passes” (often called barrier passes) that provided points of control or defence and have played a major role in the history of the Shu roads.

Furthermore, even when the watershed divides could be crossed via a mountain pass, the river valleys or sections of the river valleys were often steep, unstable and dangerous and as the ancient traffic grew there emerged a unique technology for linking valleys along mountainous cliffs to enable people and goods to pass through. These were the “Plank Roads”. Through the steepest ravines, wood or stone planks were set into the cliff face and used to construct trestle roads over which trade, armies and cultures were to flow on structures that were sometimes wide enough for horse-drawn carts and chariots to pass in two directions. Sections of Plank Road were widely used in all parts of the Shu roads. Joseph Needham and collaborators in “Science and Civilisation in China” [R.3] described the plank or trestle roads between the Wei valley and Sichuan as the “The greatest engineering work of Qin/Han road builders” and provide one of the most detailed discussions of the technology available in English. Their enthusiasm is justified not the least by the fact that although the separation of China into north and south by the Qinling has played a role in China’s history, it has not prevented China from developing a cultural and historical identity.

An early western traveller to China, the Jesuit Martino Martini, provided a rather graphic description of the Northern Plank Road between Baoji and Hanzhong in his book “Novus Atlas Sinensis” (1655, [R.18]). He wrote (translation from Latin in [W.9]):

“They rose towards the sky from the deep, with cliff holes to admit wooden beams. Planks were laid out on top to form a path from mountain to mountain, like cliff and mountain bridges, resting on beams placed in the holes sculpted out of the rock. These have formed a permanent pathway able to be used when the floods come down from the mountains. The cliff paths join up with others and where the valleys are too broad they have added supporting pillars to span them. The pillars of such bridges cover about one third of the journey. At times they are so high and the bottom is so deep that one can hardly dare to look into the gulf without horror.”

|

|

|

Figure 4: A general route (linked places) map of the Shu roads crossing the Qinling between (current) Xi’an, Hanzhong and Chengdu. |

Shu Roads in Chinese history, literature and culture

River valleys that can become corridors, if necessary by using Plank Road technology, and can be linked to other watersheds through the high mountain passes provide the potential corridors through the mountains. However, the paths by which people linked the north and south have involved not only geomorphology but also the motivations of politics, conquest, power, culture, trade and human interactions. From the combined effects of geography, terrain, history and culture emerged the historical system of Shu roads linking north and south. Seven major roads are often recognised with four crossing the northern Qinling Mountains and three crossing the southern Daba and Micang mountain barriers. They are shown in red along with other less used routes (in blue and green) in Figure 4.[3]

Naming them from west to east, the four in the north were:

The Northern Plank Road from Baoji to Baocheng near Hanzhong[4];

The Baoxie Road from Meixian in the Wei Valley to link to the Northern Plank Road near Liuba;

The Ziwu Road from Xi’an south to the Han Valley near Xixiang; and

The Tangluo Road, the shortest route to the Han Valley (but probably the hardest) from Zhouzhi to Yangxian across the Qinling near Taibai Mountain.

Those in the south were:

The Jinniu Road (“Golden Ox”) from the Han Valley to Chengdu;

The Micang Road (“Rice Granary”) south from Hanzhong southwest to Chengdu; and

The Yangba (or Lizi) Road (“Lychee”) running from Xixiang in the Han Valley south to Fuling on the Yangtse River (near present day Chongqing).

One section of road (called separately the Lianyun or “Cloud Linked” route) was a part of the main Northern Plank Road linking its Northern Section from Baoji to Fengxian with the Baoxie Road near Liuba and the lower Bao Valley section to Baocheng. An ancient Road not always listed with the main routes is sometimes referred to as the “Old Road” and is thought by some to be the route taken by the Qin Army when they conquered Shu. From near Fengxian it went along the Jialing River and followed it south into Shu. Another ancient Road was known as the Chencang Road and was supposedly the route taken by Han Xin and his troops when they “secretly marched on Chencang” while others “openly repaired the Plank Roads”. It ran north from Mianxian in the Han Valley via the Black River to join the Northern Plank Road at the Lianyun Temple south of Fengxian. Yet another named route is the well-used eastern most Shu Road from Xi’an to the Han Valley which was called the Kugu Road. In addition to these various historically significant options, a network of secondary and minor roads, often through very rough terrain, spread throughout the region. They were to no small degree the ways by which the traders of the time could avoid the tolls and garrisons along the main roads (Wiens, [R.1]). Sections of this network of roads have appeared constantly in the records and histories of the region since ancient times. The geographical extent of the network is shown in Figure 4 in which major modern towns along the routes are linked by track lines. How to define the tracks and to estimate the actual paths between the places along the roads travelled during the different time periods of history is an active area of research. Some of the progress made can be found at [W.6].

The first major “made” road (the “old Road”) seems to have been the one built by the state of Qin in the Warring States Period. The road probably included sections of what were later called the Northern Plank and Jinniu Roads but is said to have followed the Jialing River into Shu rather than go through the Han Valley. There are stories that the road was built by the state of Shu for the Qin state to bring their king a gift of “Golden Oxen” (Jin Niu)[5]. But in the end, whatever its original motivation, it simply brought the Qin army to annex Shu as well as 10,000 families of settlers from Qin. This conquest took almost a hundred years to the mid-fourth century BCE, and vastly increased the power of Qin. Qin developed the resources of Shu, including the important irrigation structure at Dujiangyan (Shi Ji, 29; see Sima Qian, as translated by Burton Watson, [R.10]) and Shu became a "rice bowl" for Qin. The Shu roads through the mountains provided essential supplies to Qin as it united China under the Qin Dynasty in 221 BCE.

In the Qin, Han and the Three Kingdom (220-230 CE) periods, well engineered Plank Roads were built, repaired and extended very widely through the Qinling and Daba mountains and in easier terrain to the south, paved stone roads were consolidated and maintained to form part of China’s Postal Road system. With the possible exception of the Yangba Road, all of the major roads mentioned above were completed and used during this time. During the Western Han Dynasty, the Shi Ji, 29 (Sima Qian, [R.10]) records how the state engineers convinced the Emperor Wu to fund major works and extend the Baoxie Road so that rice and other materials could be brought to the Guanzhong via the Han River and the Bao and Xie rivers with a short linking land road across the Wulipo divide. As recorded by the Royal Historian Sima Qian [R.10] “When the road was finished it did in fact prove to be much shorter and more convenient than the old route, but the rivers were too full of rapids and boulders to be used for transporting grain”.

A major event in Chinese history involving the Plank Roads occurred when the Qin Dynasty was overthrown by a coalition of rebels in 206 BCE. The “Grand Hegemon” Xiang Yu was fearful of another king setting up in the Qin capital at Xianyang near present day Xi’an in the “Land within the passes” (Guanzhong). He banished his major rival, Liu Bang (Figure 5), to be King of the three states of Han (around present day Hanzhong), Shu (present day Sichuan) and Ba (present day Chongqing). There had been an agreement that the general who captured Xianyang (who turned out to be Liu Bang) would rule the Guanzhong, but Xiang Yu argued that Han, Shu and Ba were also “lands within passes” (Shi Ji, 7; Sima Qian, [R.10]) and sent Liu Bang off (he hoped) across the mountains for a long stay.

|

|

|

Figure 5: A painting representing Liu Bang, the first Han Emperor or Gao Zu. |

Liu Bang and his troops travelled on Plank Roads to reach Hanzhong. On the advice of Liu Bang’s advisor Zhang Liang (who knew the Qinling well and has his temple near present day Liuba on the Lianyun Road) they burned the Plank Roads after they passed to discourage pursuers and convince Xiang Yu they did not intend to return. At Hanzhong, on the site of the present day Hanzhong Museum is the Hantai or Han Platform where Liu Bang proclaimed the Han Kingdom. As it turned out, it was the also the platform from which Liu Bang launched his armies to reunite China as the Han Dynasty and became the first Han Emperor. To do this he convinced his best general Han Xin not to return to the civilised East but to become Generalissimo of the Han forces. Han Xin secretly led his troops north along what is now called the “Chencang” Road to attack Chencang (“Chen granary”), the ancient name for present day Baoji on the Wei River. While he crept north, others openly set about repairing the Plank Roads burned previously by Zhang Liang to focus the attention of Xiang Yu’s forces away from Chencang. This historical action is remembered in a famous Chinese idiom “openly repair the Plank Roads, secretly go to attack Chencang[6]”. It is one of the famous Chinese “36 Stratagems”. There is a lot more that could be said about this time of history, but it is far too much for this introduction and there are also many places to find out all you wish. Interested people are referred to translations of Chinese books such as the Shi Ji (Sima Qian, [R.10]) or to more recently published histories such as Twitchett and Loewe (The Cambridge History of China, [R.11]) to explore the tumultuous events of these times.

A strikingly similar event occurred after the final fall of the Eastern Han in 220 CE. At this time, China split into the Three Kingdoms of Wei (a northern kingdom including former capitals Chang’an in the Guanzhong and Luoyang), Wu (with its capital on the site of present day Nanjing) and Shu with its capital at Chengdu. The king of Shu was Liu Bei and he saw himself as the successor of the Han. His Kingdom was called “Shu Han” and he declared himself Emperor of China. Just as his ancestor Liu Bang had a smart advisor called Zhang Liang, Liu Bei also had a clever Prime Minister called Zhuge Liang. Zhuge Liang was also known by his style Kongming and by an early appellation of Wolong or “Sleeping Dragon”. During his life he was given the title of Wuxiang Hou or the Marquis of Wuxiang, a township north of Hanzhong. Following his death, he was apparently entitled by the second Shuhan emperor as the “Faithful Martial Lord” or Zhong Wuhou and to this day, his ancestral temples and memorials often refer to him as Wuhou, the Martial Lord. Zhuge Liang almost emulated Liu Bang’s success for his master in a series of raids against Wei across the Qinling and into the Guanzhong but in the end he was not successful and Shu Han as well as Wu eventually fell to Wei.

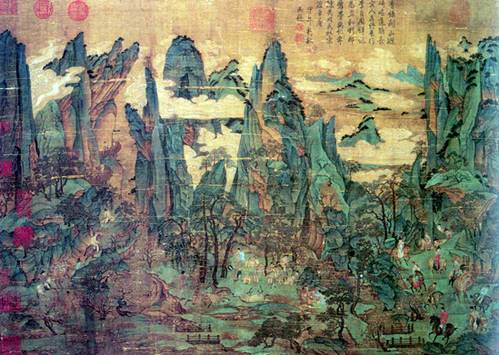

The stories of the times have become part of Chinese culture in the form of a famous historical novel (which is at least as much novel as history) called “San Guo Yanyi” translated by Moss Roberts [R.12] as “Three Kingdoms” (Figure 6 show a famous battle near Dingjun Mountain by the Han River). To find out how the Shu Roads also formed a stage for a romance of stirring history and heroic deeds you can do much worse than to read this book. For the official history of these areas and events at the end of the Han there are more accurate accounts in English such as in works by Prof. Rafe de Crespigny [R.13], [R.14] and other publications and translations based on the historical records of the time.

|

|

|

Figure 6. A scene from the Romance of the Three Kingdoms. |

The Tang Period (618-907 CE) saw the Plank Roads, including the central Tangluo Road between Chang’an and the Han River, remain part of literature and history as statesmen and poets such as Li Bai (also known as Li Bo) were sent to exile in Shu away from the court(s) in Chang’an and Luoyang. On one such occasion, the Poet Li Bai wrote a famous poem called “The Road to Shu is Hard” and a translation (in Minford and Lau, [R.15]) will give its reader a flavour of what it was like to travel through the Qinling at that time. In the poem, Li Bai describes the Plank Roads as “ladders to heaven”:

“When earth collapsed and the mountain crashed,

the muscled warriors died.

It was after that when the ladders to heaven

were linked together with timber and stone.”

The Tang Emperor of the time (Tang Xuanzong) also travelled the roads to Shu in exile as rebels invaded the capital. He fled Chang’an to the Han River using the Baoxie Road and came back later along the Jinniu Road as an abdicated monarch and without his favourite concubine. His favourite, Yang Guifei, had been forced to kill herself at Mawei Po as his army fled with him from Chang’an to Shu. The Yangba Road to Fuling was said to have been built earlier by this enchanted Emperor to bring fresh Lychee from the south of China to Xi’an for the extravagant imperial concubine. The Song painting in Figure 7 shows a “map” of the emperor’s journey to Shu and it is possible to see Plank Roads winding up the steep and sharp ridged mountains on the left side of the image.

|

|

|

Figure 7: Tang Ming Huang’s journey to Shu (US Library of Congress) |

On the way back from exile in Shu, the Emperor wrote a poem at “Sword Gate Pass” (Jianmen Guan in northern Sichuan just south of Guangyuan) in which he wrote (perhaps in remorse for his failing to be a virtuous Emperor)[7]:

“Our tour complete our carriage returns

to Sword Gate’s cloud-barred peaks

its mile-high screen of folded jade

its cinnabar walls breached by heroes

our pennants weave through the tapestry of trees

ethereal clouds brush past our horses

rising to the times depends on virtue

how true is this description?”

The story of the Emperor Tang Xuanzong’s love for Yang Yuhuan or “Imperial Consort Yang” was recorded in a Tang poem by the Poet Bai Juyi and is called (in English) the “Song of Eternal Regret”. An excellent English language translation of Bai Juyi’s poem is also included in the volume compiled by Minford and Lau, [R.15]. But its language is oblique and cryptic, so some have alternative theories, one of which has been explored by Shui Xiaojie in his Chinese language book “Short Stories of the Han River”. The Short Story[8] involving Yang Yuhuan has been translated and made available at the Qinling Roads to Shu Website in a document at [W.7]. Shui Xiaojie explained the idea as:

“I was much more interested in some things that the official history does not include. One of these is the possibility that a very famous Lady, Yang Guifei, while fleeing from home, passed along the Tangluo Road. It is said among the local people that the person who strangled herself at Mawei Po in the 15th Tianbao year of Tang Xuanzong (756 CE) was only a scapegoat. When the Emperor Xuanzong dispensed with the love of his life, and went via the Ancient Baoye Plank Road to Sichuan, they say the 38 year old Lady Yang Yuhuan had secretly arranged to go by the Tangluo Road and Han River to reach Yangzhou. In the end she travelled over the sea to reach Japan, so that up to the present day in that island country, in Yamaguchi prefecture, is “Yang Guifei's home village”, where there are still many relics.”

If you find such popular legends of the unofficial history of ancient Qinling Roads to Shu interesting you are welcome to access the translation at [W.7].

In the Song (960-1279 CE), Yuan (1271-1368 CE) and Ming (1368-1662 CE) times the Shu Roads continued as major routes of communication between north and south as well as roads travelled by armies of invasion and liberation moving between the north-west and the south-west of China. Over that time, despite the many wars, the roads gradually became paved and stabilised and the Lianyun road and Bao River valley became sections of the main Post Road from Xi’an to Chengdu. The description of the main post road from present day Baoji to Chengdu by Marco Polo (Yule and Cordier, [R.17]) is geographically accurate and an indication of the importance placed on secure and well paved road communications by the Mongol Yuan Dynasty. The Ming maintained the roads, giving particular attention to the main Postal Road. This has often been called the “Great Road” as it stretched from Beijing to Chengdu and the section involving Shu Roads comprised the Northern Plank Road and the Jinniu Road. Despite this, over time there was reducing interest in the west of China and in road traffic as the Yangtze valley with its river and canal transportation became the centre of the economy and the area between Nanjing and Beijing became the central place of the empire.

At the end of the Ming in 1644 CE there was also a breakdown in social order with rebellions by peasants and minority peoples. The population of Sichuan was decimated[9] by the combined efforts of the rebel Zhang Xianzhong (also called “Yellow Tiger”) and the Qing army that came to re-conquer Sichuan, and consequently the roads fell into disrepair (see Herold Wiens, [R.1]). Starting in the Qianlong reign of the Qing (1662-1911 CE) period, Sichuan was repopulated, including by Hakka people from the south of China. As this happened, the north-south roads were repaired and many travellers, artists and writers left detailed accounts and drawings of the mountain roads of the day and the natural wonders they found along the way [W.8]. The Shu Roads as consolidated and repaired at this time were, despite the ravages of the Taiping Rebellion and the decay at the end of the Qing, mostly still in use during the early and middle years of the Republic of China (Min Guo 1912-1949 CE).

During the 2000 years history of the Shu Roads, stories about people who moved or lived along the roads, the geography of the mountainous regions they passed through and local events were all carefully recorded and dated. The records include literature and art, calligraphy, artistic scroll maps, the records of travellers and Stele and most importantly the “Fang Zhi” or the regional and local gazetteers of everything that happened to people, the environment and everything else down to the local level. Much of the information is geographical and included maps but it was rarely mapped in the sense of modern mapping and was not always consistent or accurate. The rich local records are nevertheless a unique and significant source of written information on the Shu Roads and allow us to recreate and experience its events even after many years.

Reports by Western travellers on the Shu Roads

Following the Opium Wars, the Taiping Rebellion and the Treaty of Tianjin, merchants, missionaries and military travellers visited the west of China in search of a range of adventures and information to report to other eager business people, missionaries and military commanders. Some of them visited the Qinling Mountains and travelled on the Shu Roads. However, in the preceding 300 years, Catholic Missionaries had already been moving into the interior of China – although not without problems. Among the travellers listed here who visited the Shu Roads are eight (one group and seven individuals) who have been generally recognised and quoted extensively by previous writers, especially by Herold Wiens [R.1]&[R.2], Joseph Needham [R.3] and more recently by Hope Justman [R.4]. Joseph Needham also travelled the Shu Road from Chengdu to Shuangshi Pu (present day Feng Xian, probably on the new motor road) in the 1940’s so he was also a China traveller as have been Herold Wiens and Hope Justman. There have almost certainly been many others – especially among missionaries – but the travellers discussed in this section left published notes and papers that can be accessed today and they visited the roads before motor roads arrived after ca. 1925. Their publications contain useful information about China and Chinese of the time, of the contemporary historical events and of the natural resources as well as the geology and geography of the Shu Road region as well as discussions of sections of the Shu Roads. In this introduction, we will only briefly mention places they visited and books they wrote and leave the rest to other more comprehensive descriptions of the travellers and their legacy – including their own journals.

|

|

|

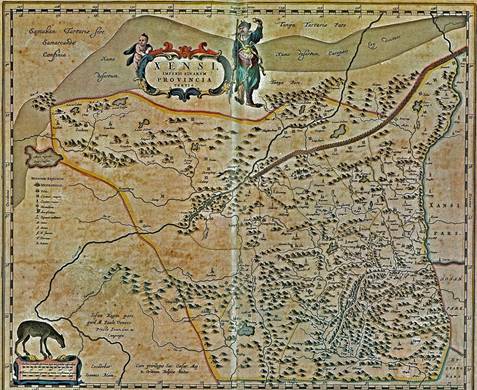

Figure 8 : Map of Shaanxi from Martini 1655 “Novus Atlas Sinensis”. The main Northern Plank road runs SSW near the bottom right. |

Catholic Priests on the Great Road (1635-1935)

Among the earliest European travellers to China (at that time called “Cathay” in the west) were Catholic Missionaries who moved into the west of China to spread Christianity[10]. The activity started with Marco Polo’s c.1290 account of travels in China, which many Priests who arrived later had read avidly to find out about China. Among the earliest Catholic priests who worked in Shaanxi were Jesuits Fr. Étienne Faber and Fr. Martino Martini. In 1635, Fr. Faber went to Hanzhong to establish the first mission to southern Shaanxi. He travelled through the Qinling Mountains from Xi’an, almost certainly along the Lianyun Road, to arrive in Hanzhong. Martino Martini left for Rome in 1651 where he reported on progress of the mission and published an atlas of new maps of China (Martino Martini “Novus Atlas Sinensis” [R.18] & Figure 8) in 1655, which included the previously quoted version of the history of the Plank Roads between Chang’an and Hanzhong in some detail.

The Franciscan Fr. B. Basilio Brollo came in 1701 to continue the work in the west as did Franciscan Fr. Jean Basset in 1703. Fr. Basset was Pro-Vicar of Northern Sichuan and must have travelled the Jinniu Road. In 1702, in a report to Rome, Fr. Brollo wrote (statements in brackets are additions to clarify the text):

“The road to Hanchung (from Xi’an) takes 13 days, 7 by arduous hills and cliffs, as previously described by Fr. Martino. I do not think the world has any others with this sort of route. There are balconies on poles for up to 25 Li, there are also many bridges and roads clinging to the rocks and rivers and supported with timbers at the base of the mountains. Some of the rivers go to the Han River, others to the Hoei (Wei), which in the north enters the Hoang ho (Yellow River or Huang He).”

Fr. Brollo also recorded a more detailed description of the stages of the road to Hanzhong that was no doubt aimed at helping others to plan and make the journey. Out of this later period in 1736 came the summary of Jesuit achievements by Jean-Baptiste du Halde [R.19] that includes the Jesuit observations of the day, including the story of Fr. Étienne Faber, summaries of the Plank Roads and the Kangxi Maps [W.12]. But after this time the orders fought each other and following the “Chinese Rites Controversy” the missions were generally unwelcome in China until the 19th Century. After the Opium Wars between 1842 and 1860, the Vincentian l’Abbé Armand David came to the Han River in 1873 and published the findings of his journey in “Journal de Mon Troisième Voyage d’Exploration dans L’Empire Chinois” [R.20]. L’Abbé Armand David CM was a naturalist missionary as well as traveller and recorded the Qinling wildlife as well as geology and observations of China [W.13] before embarking by boat down the Han River to Hankou. The later founding and development of a Franciscan mission at Guluba in Chenggu County was also a significant event at this time. Guluba had been the site of a Christian Church since Fr. Étienne Faber visited Hanzhong. In 1888 Guluba was expanded into a fortified settlement by Italian missionaries who remained there for another 50 years. The involvement of Catholic Missionaries with the Qinling and Ba Mountain roads adds important information to the tales of other travellers and material such as the letters collected in Wyngaert’s “Sinica Franciscana” [R.21] have provided us with early western views of the Plank Roads. A document has been written to outline this history as it relates to the Shu roads with focus on the Han River and it can be accessed by the Web link at [W.9]

Alexander Wylie (1868)

Alexander Wylie travelled from Chengdu in Sichuan to Da’an in Shaanxi along the Jinniu Road. He wrote a paper called “Notes of a Journey from Ching-Too to Hankow” which was published in the Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society of London in 1869 [R.22]. In the paper he described the geography of inland China and its roads and the waterways. He also listed places visited to village level and paid special attention to river traffic. His account drew praise from Ferdinand von Richthofen (see below), another early traveller, who instead of describing the road to Chengdu from the Han Valley using his own observations referred readers to Alexander Wylie’s paper. The places Wylie visited along the way have been collected in a number of documents and a Web Page has been created with a general description of his journey and access to the related materials. It can be found at web reference [W.10]. These materials have been supplemented by findings and materials collected during a field visit in 2012. As described in [R.22], after they reached Da’an on the upper Han River in Shaanxi, Wylie and his party made significant use of river transport to travel to Hanzhong and then to return to Hankou on the Yangzte River (from where they had started). However, to avoid a dangerous and rapid-filled section of the river between Yangxian and Shiquan, they went overland using an important linking road through the Han Basin. The route went from Hanzhong to Xixiang and on to Shiquan and is discussed in more detail documents which can also be found at [W.10]. The field visit included a visit to a working Mosque in Shahe Kan where Wylie had reported a well-established local Muslim population.

Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen (1870-1873)

Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen, (an Uncle of the Red Baron of WW1) travelled extensively in northern China between 1870 and 1873. He was collecting information for both commercial and scientific interests and sponsors. He was a geologist and very interested in the diaries of Père Armand David. In 1872 the Baron travelled from Baoji to Chengdu along the Northern Plank Road and Jinniu Road. Père Armand David informs us that von Richthofen stayed in Baocheng but did not go into Hanzhong. He published an extensive and very interesting set of letters in English (von Richthofen, “From Si-ngan-fu to Ching-tu-fu” in “Letter on the Province of Hunan. (Reports III. – VII on other Provinces of China)”, [R.23]). However, the majority of his detailed reports were in German. Herold Wiens knew both German and Chinese and his Thesis (Wiens, [R.1]) contains a list of places and information along the route using material collated from all of the reports published by Alexander Wylie, Ferdinand von Richthofen, L’Abbé Armand David and Sir Eric Teichman. Herold Wiens’ collated list is therefore almost certainly the most comprehensive guide to the northern and southern sections of the main route. This route has been the “Da Lu” or “Great Road” since at least the Yuan period when it was travelled by Marco Polo (as outlined by Yule, H. and Cordier, H., [R.17]). Although Herold Wiens includes notes on geology, geography, geotechnical evaluation, barrier passes and many places in his description, the collation is not always as detailed as the original traveller reports which therefore still provide added value and bear reading even now.

|

|

|

Figure 9 : Alexander Wylie found the Han River hazardous and Père Armand David and the Russian Expedition of Col. Sosnovsky were boat-wrecked in the rapids. (From [R.24]) |

M. L’Abbé Père Armand David (1872-1873)

Père Armand David made three major journeys in China studying the wildlife and collecting specimens of the flora, fauna and geology. He was the first European to see and study the Giant Panda and gave his name to a species of deer (Père David’s deer) previously unknown to Europeans. His third journey in 1872-1873 included investigating areas of the northern and southern slopes of the Qinling Mountains. The main report of his activities was published in 1875 as “Journal de Mon Troisième Voyage d’Exploration dans L’Empire Chinois” [R.20]. After investigations in the Lao and other valleys on the northern slopes of the Qinling, he decided to go the Hanzhong basin on the southern slopes before returning to Hankou by boat via the Han River. Perhaps Wylie’s successful journey to Hankou suggested this to him. He was aware that Baron von Richthofen had just (1872) travelled through the Qinling using the Northern Plank Road so he decided to take another route along what is usually called the Baoye Road [W.13]. He started on February 15, 1873 and travelled through today’s Shitou River valley, passed the Guangdang Mountains and climbed through the Wuli Po. Reaching the tableland he stayed at a village called Jutou Jie which is the site of the present day county seat of Taibai Xian. He notes that there was a road from here to Guozhen in the Wei Valley which had also interested von Richthofen. They continued along the Bao River through Jiangkou to join the main Lianyun Road. Von Richthofen had already passed this way in 1872 and he later read David’s descriptions – especially of wildlife and geology – with great interest and most likely included material from them in his later reports. Père Armand David stayed for some time near Chenggu and Mianxian and made expeditions into the mountains. Some of his activity is included in the document on Catholic Priests to be accessed at [W.9] and his travels in the Qinling can be found at [W.13]. He finally went by boat on the Han River from Chenggu to Hankou. Unfortunately, his boat was wrecked on some fierce rapids that occur between Shiquan and Ankang. He lost many valuable specimens – but survived to write his diary.

Col. Sosnovsky’s Russian Expedition of 1874

Russian travellers accompanying Col. Sosnovsky’s expedition came to Hanzhong from Hankou along the Han River by boat in 1874 and then travelled to Gansu and Lanzhou via Mianxian, Liuyang, Huixian and present day Tianshui (Qing period Qin Zhou) along what is today Highway G316. The report of the expedition, including wonderful gravure productions of sketches from the places visited and drawn by Dr. P. Piassetsky was published in 1880 in Russian and was quickly translated and published in French (1883) and English (1884). The English title is “Russian travellers in Mongolia and China.” (Piassetsky, [R.24]). Apart from the linking roads through the Han Valley, they did not travel by the main Shu Roads but did leave significant information on the secondary roads through Gansu that became so important near the end of WW2. The description of the Han River route from Hankou to Hanzhong is detailed and valuable. The interactions between the Upper Han and the Lower Han and the shipping information from these times are all important in Shu Road research. The difficulties of river travel were recorded in the shipwreck that nearly finished the expedition just north of Shiquan (see Figure 9). The expedition included a professional photographer (A.E. Boyarsky) some of whose early photographs of Hanzhong have been included in a recent publication in Chinese by Sun Qixiang [R.33]. A report of a meeting between the Russian expedition and local Christians near Hanzhong has been included in the document about Catholic Priests on Shu Roads at Web reference [W.9]. The only traveller discussed here who did not meet local Christians and their local priests when in Hanzhong seems to have been Alexander Wylie. But his stay in Hanzhong was short and wet.

Mrs J.F. Bishop (Isabella L. Bird) (1897)

Isabella was an “intrepid” lady traveller of the 19th century whose book outlining her adventures travelling in the west of China and into the regions where ethnic Tibetan peoples live in the west of Sichuan is a classic as well as highly informative and readable. It was published in 1900 and is called “The Yangtze Valley and Beyond.” [R.25]. It includes travels along the Yangtze River to Sichuan and through Sichuan to the western mountains. Her description of Chinese people and their ways is objective and not as “distant” or prejudiced as are descriptions made by many of the male writers of the time. Her contribution to knowledge of the Shu Roads is less than her contribution to knowledge of and appreciation of Chinese. She travelled to Baoning (present day Langzhong) in Sichuan and north to a rest station for missionaries. From there she travelled cross country to join the Jinniu Road (part of the Da Lu or Great Road) a little south of Old Jiange (present day Pu’an Zhen). She then travelled south along the road to Mian Zhou (present day Mianyang). Although her journey on Shu Roads was short, it contains very detailed accounts of the Cedars that lined the ancient Jinniu Road in Sichuan and its combination with information provided by Alexander Wylie, von Richthofen and Eric Teichman has been very useful for Shu Road research and the development of maps. The account written by Isabella Bird seems to have motivated Hope Justman ([R.4] and [W.3]) in her more recent journeys along stretches of this beautiful section of the southern Shu Roads. Ancient bridges like one she recorded by an early photograph in her book can still be found near Pu’an Zhen (see Figure 10) today.

|

|

|

Figure 10 : Ancient bridge photographed north of Pu’an Zhen in Sichuan in 1897. Bridges like this can still be found in this area today. (From [R.25]) |

Sir Eric Teichman (1917)

As a Consular Officer, Eric Teichman made a series of journeys through north-west China in 1917. His book “Travels of a Consular Officer in North-west China” [R.26], published in 1920, has extensive material on the political and social conditions in China at the time. One reason for making his journeys was to investigate the success or otherwise of the suppression of Opium cultivation. His association with the Shu Roads came about as he took a route that maximised his travel to places off the major roads. His party left the main road at Tongguan and headed into the Qinling to go to Xing’an or present day Ankang. They went first to Luonan Xian, then cutting across the direction of most existing roads they reached present day Shangluo Shi (Qing period Shang Zhou). He then headed west over yet fierce mountains to Zhen’an Xian where he reached the easternmost Shu Road called the “Kugu Road”. Teichman set out along the Kugu Road heading for Xing’an (Ankang) and went as far as Lianghe Guan. There, despite his party’s desire to take to boats, Teichman insisted on setting out another way. They climbed to a high pass and arrived at Maping He. Accompanied by the Magistrate of Xing’an they then climbed and slid more than 30km to arrive at Xing’an Fu. Teichman and his party went by road to Hanzhong through Shiquan which he says forms a junction of the present road with the Ziwu Road from Xi’an. After Shiquan, the road followed by Teichman is the same as that used in the opposite direction by Wylie when he avoided the rapids between Yangxian and Shiquan. On the way to Hanzhong, Teichman visited the Italian catholic Mission at Guluba which had been opened since the time Alexander Wylie travelled the road. The road they followed had been an important linking road in the Han Basin at one time but had fell from favour sometime in the late Qing. From Hanzhong, Teichman decided to travel to the Wei Valley via another of the famous Shu Roads – the Tangluo Road. A web page and comprehensive set of documents and materials based on this journey can be found at Web reference [W.11]. Teichman’s travels through North and West China in 1916 and 1917 were extensive. As well as his excursions along the back roads such as the Kugu Road in the east and the central ancient Tangluo Road, he also made a classic journey (probably similar to that of Marco Polo) from Xi’an to Chengdu via the Wei Valley main road, the Northern Plank Road, including the Lianyun Section and the Han Valley linking road, and finally along the Jinniu Road in Sichuan. His careful description is precise and detailed and includes stage distances (in Li) and recorded altitudes. It is not clear if his diary was used by Herold Wiens but when it is combined with Wiens’ and various other descriptions of the main road, the route followed and the towns on the way in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s can be established with some accuracy.

Brigadier-General George Pereira (1921-1922)

Brigadier General George Periera made a number of journeys in China. He was Military Attaché at the British Legation in Beijing in 1905-1910, where he learned Chinese. In 1921, Pereira’s greatest achievement was when he became the first British traveller to reach Lhasa from China and the first European to succeed in this objective since the visit by L’Abbé Huc in 1845. After reaching Lhasa he went south into India and then back through Burma into China trying to complete a circuit of access routes. Unfortunately, he died in Yunnan in 1923 before he completed his objective. His brother, Major-General Sir Cecil Pereira read a summary paper of his travels to the Royal Geographical Society in 1924 [R.27]. His papers and diaries were also edited and compiled by Sir Francis Younghusband and published in 1926 as “Peking to Lhasa”. [R.28]. His book provides very useful information about a number of Shu Roads. As part of his voyage to Lhasa, Pereira needed to travel from Xi’an to Chengdu. Because of security concerns and the turmoil that existed in early Republican China, General Pereira travelled to Hanzhong by the Ziwu Road rather than the Northern Plank Road from Baoji. His description of the journey started with the ascent into the Qinling Mountains via the valley of the Fengyu River. He travelled via Guanghuo Jie and (East) Jiangkou to Xunyang Ba and Ningshan Xian. He then travelled to Lianghekou but varied the journey by going to Jinshui He where the Yangxian magistrate was waiting for him. From there he travelled along the Han River to Hanzhong. From Hanzhong, he again had to use a secondary road through the Micang Mountains (the ancient Micang Road) as the Red Lantern Society (remnants of Boxers) held the main road. His description provides important and unique information on the back route across the mountains to Nanjiang. Pereira went by river transport from Nanjiang to Ba Zhou (present day Bazhong), then by road to Baoning Fu (present day Langzhong Shi) and on to Chengdu. At this point he left the Shu Roads, but the longest and hardest part of his journey was only just starting.

Modern “Shu Roads”

The ancient engineering innovations and their enterprise have continued to inspire modern Chinese as since 1949 they have built a new country and in these modern times there have been equally great engineering feats achieved as the present day “Shu roads” have come into existence. But instead of porters and mules which were still the main form of transport on the Shu Roads in 1934, as shown in Figure 11, the modern Shu Roads are hosts to an endless flow of trucks and cars moving people and goods rapidly throughout China across and through mountain ranges and over wide rivers.

|

|

|

|

Figure 11: Travelling from Baoji to Hanzhong in 1934 (Frank Moore collection) |

|

According to the English language Shanghai Sunday Times (Nov. 12, 1932)[11], in 1932 there were only 1269 miles (2040 km) of automobile roads in Sichuan and 235 automobiles, and in Shaanxi there were 1808 (2910 km) miles of automobile road and 414 automobiles. China as a whole had 39,350 miles (63,350 km) of automobile road and 43,834 automobiles. In 1952, the total length of roads in China had doubled to 126,700 km. By contrast in late 1997 there were 1.226 million km of road in China (about 10 times what it was in 1952) and 57,570 km of railroads[12]. Since then there has been a further massive growth of Tollways covering the country, including the recently completed Xihan Tollway that crosses the Qinling using 110km of tunnels and as many overpasses. It has been a dramatic change.

Herold Wiens [R.1] suggests that the first significant modern motor road building in China was carried out with funding from the American Red Cross Society in 1920-21 in Hebei, Henan, Shanxi and Shandong Provinces. One of the people working on these roads was the General Joe “Vinegar” Stillwell who was later US military liaison during the war with Japan. The road building along the Old Post Road started in the 1930’s. It originated as part of an ambitious Shaanxi-Guangxi road planned by the National People’s Conventions held in 1929-1931. Eventually, however, it was only the section from Chengdu to Xi’an that was built. According to Herold Wiens [R.1] & [R.2], the new motor road from Chengdu to Guangyuan was completed by 1935 and followed the old Jinniu Road. This is today’s Highway G108. The shorter and easier sections through the Han Valley were also completed by about the same time. In the north, a new road was built through the Wei River valley from Xi’an to Baoji via Fengxiang to the foot of the Qinling by closely following the old Road; and then continued on into the Qinling to reach Fengzhou by sometime in 1935.

But the terrain making up what was the linking route of the former Lianyun Road was the hardest and most expensive section to tackle and it was not until the pressure of war with Japan increased its priority so that it was finally completed in 1941. This occurred after the fall of the Burma Road when its operational use was critical to enable materials and soldiers to move between Sichuan (the wartime capital of China was at Chongqing) and the north to access and transport heavy materials coming from Russia (Herold Wiens, [R.2]). The Shu Road that had been the main “Post Road” since at least the Yuan period was thereby finally replaced by more modern materials. But it was done only through the major stimulus of the war effort against Japan and heritage photographs show that the road to Shu was still “hard” at that time (see Figure 12). Not very long after it was opened, Joseph Needham travelled the northern road by truck in 1943 [R.34]. His descriptions of the hardships faced by the road users shows that even after the new road arrived, endurance and ingenuity were still useful qualities to have on the Shu Roads. His convey also included Sir Eric Teichman whom he and Chinese referred to as “Old Tai” (老台).

|

|

|

Figure 12: The new road to Shu was still hard in 1937. Taken from Chicken Head Pass above the Stone Gate. |

An east-west railway connection between Wuhan and Hanzhong was also completed as part of the war effort. Since 1949, a major railway linking north and south was constructed crossing from Baoji to Chengdu via Tianshui for the most part along the track of the “Old Road” along the original Qin road down the valley of the Jialing River. Extensive road building over the routes of many of the previous Shu Roads was also undertaken with great effort and facing great hardships to open up road traffic. In the same period, large dams were built at the two ends of the Baoxie Road to generate electricity, control floods, irrigate land and produce food. The “Plank Road Spirit” of ancient times could well have helped in the success of these more recent efforts. It is now possible to go from Hanzhong to Xi’an in two hours using the recently opened Xihan (Xi’an to Hanzhong) Tollway – but through some of the world’s longest modern tunnels and overpasses rather than over ancient Plank Roads.

The People and Environment of the Shu Roads

The Shu roads were nothing like the freeways of today that maximize speed of travel and traffic flow, minimise service points to the essential and avoid stops at towns and villages. In the past, a day’s journey was not very far by today’s standards but was much more tiring for people and horses and so the routes supported a significant population servicing the needs of people, animals and goods as well as taking advantage of the access to materials provided by the roads and the protection provided by the authorities stationed along the route. Where the extensive imperial postal services operated, the modern towns often still carry names indicating the original reasons for their settlement. These include Zhan (站, stopover), Pu (铺, relay station) and Yi (驿, post station) as places that supported the provision of fresh horses and rest for travellers and Tang (塘, embankment) or Ba (坝, barrier) which could indicate an inspection (or duty) point. The mountain passes through which people passed between watersheds were natural for fortification and location of inspection points and many modern towns have Guan (关, gate) as part of their name from their association with the fortified passes. Others may have Zhen[13] (镇, garrison) or Ying (营, barracks) in their names indicating at one time there were soldiers stationed there. The secondary roads also supported a population servicing the traffic and travellers as many people wished to avoid the inspection points (the modern equivalents of the Toll Stations along the highways) and took to the mountain roads. Perhaps it was a more interesting population that grew up on these secondary tracks.

But life along the Shu roads was at least as hard for those who lived there as for those travelling them. The mountains were the scene of fierce winters, floods, landslides and earthquakes. In early times wild animals made life dangerous for people and domestic animals. But perhaps the most dangerous times were when armies moved north and south along the roads. At these times, rebels, dynasties and invaders battled for dominance and people along the roads suffered. The relatively small areas of arable land had to support the population through these events as well as during less difficult times. The first road apparently brought the Qin army to conquer Shu and ever since as the Three Kingdoms vied for power, the Tang Dynasty battled or escaped from rebels, Song battled Jin and Mongols invaded China the region periodically became a battleground. The armies of the Ming and Qing ruthlessly recovered territory as the dynasties started out but later could do little to stop rebel armies wandering through the mountains destroying towns along the way as each dynasty declined. In all cases it was the people living there who bore the brunt.

The attractions of trade and travelling as well as the protection afforded in stable times by garrisons and walled cities clearly outweighed the possibility that these hard periods of change would occur. Over the history of the Shu Roads, the Han people tended to trust in the strength of the established towns while other peoples occupied the remote valleys where they were safer but life was harder. Among these minorities, the Qiang people (羌族) have been closely associated with the secondary Shu roads that moved goods to Chengdu via less accessible but probably tax free pathways. The Qiang is an ancient Chinese minority that has claimed associations with the Xia Dynasty (夏朝) and the famous Da Yu (大禹, a legendary King who tamed the waters of the Yellow and other rivers) who some believe came from Beichuan in Sichuan. But in more certain history Qiang people were brought to Gansu from present day Qinghai by the Han to settle and farm but rebelled as the Han dynasty ended (Rafe de Crespigny, [R.13]). In the mountains between the Wei River and Chengdu the Qiang people have lived in the remote valleys. In the Ming and Qing periods, the town of Ningqiang (宁强) in southern Shaanxi was called Ningqiang Zhou (宁羌州) with the “qiang” part of the name being the character for the Qiang Minority. It has been suggested that it was named to indicate to Qiang people that it was a safe place to come to from the mountains – although other explanations have been given. As part of the rebuilding following the 2008 earthquake, Museums of Qiang Culture have been established in Ningqiang in Shaanxi and Mianyang in northern Sichuan

The areas surrounding the Shu roads also contain some of China’s most remote and extent wilderness areas. Many areas have been exploited, such as for timber and resources, but not to the degree seen in some other parts of China. In modern times, large areas have been set aside for wildlife and environment conservation including conservation areas for Pandas, Macaque monkeys, Golden Monkey, Crested Ibis, Musk Deer and many other species of wildlife, some endangered and many still abundant. The southern slopes of the Qinling Mountains near one of hardest of the ancient Shu Roads, the Tangluo Road, have also provided an environment where rare species, such as the Qinling Panda, are to be found. The area through which Sir Eric Teichman passed on his journey in 1917 is now a major conservation park as described by one of the Stories in the document at Web reference [W.7]. According to Ma Qiang in 2008 in “Evaluation of Wildlife in the Vicinity of the Shu Roads in the Tang and Song Dynasties” [R.30], as late as the Song period, tigers, including the South China Tiger, and elephants could still be seen near the Shu Roads in Sichuan. The south China tiger and elephants can no longer be found in the wild, however, there are still areas in Sichuan where historical sites and temples, climbs to peaks and descents into valleys coexist with some of the wildlife described by Ma Qiang.

The dense forests of the Qinling, Ba, Micang and Longmen mountain ranges have been remarked upon and admired for a thousand years. Marco Polo (Yule and Cordier, [R.17]) was greatly impressed by the dense forests of these mountains although he did not mention the Plank Roads. The dense mountain forests are also to this day source areas for unique components of Chinese herbal medicine. Traditional Chinese medicine has been a major industry of the areas covered by the Qinling Plank Roads to Shu throughout their history. Conservation of forest resources has been a tradition in this part of China as evidenced by the records of Stele in the Micang Mountains. These records have been discussed by Zhang Haoliang in 1990 in “Notes on historical environmental records: Collected forest stele of the Ba Mountains” [R.31]. The changing extent of forests and the cycles of responsible forestry can be found in the detailed records of the Fang Zhi, or local records. It seems from such records the current forest cover reduced significantly following years of fighting and rebellion in the 19th century as the Qing dynasty declined and lost its authority throughout China and internationally.

In the Qinling Mountains is to be found the Temple of the Han Prime Minister Zhang Liang. Zhang Liang is famous in the history of Daoist philosophy and the Qinling Mountain Ranges have been a bastion of Daoism for much of written history. Buddhism seems to have gained a few footholds, but generally stayed close to the main roads with major centres such as Maiji Grottoes (near Tianshui) to the north, the Lingyan Si near Lueyang in the middle, the Qianfo Grottoes at Guangyuan to the south and with various temples and grottoes strung along the roads between. In the remote mountain valleys, the Daoists seem to have held sway from Baoji through to the Wudang Mountains on the lower reaches of the Han River. As time passed, temples, monuments and family tombs dedicated to the many famous people and events grew and flourished along the routes. Cai Lun, the person who discovered modern paper, Zhang Qian, the person who brought reports of northern and southern “silk roads” to Chinese history, Ma Chao, Zhuge Liang, Zhang Liang and Wu Zuotian are all connected with the mountain roads.

As Han culture and technology spread south from the Wei river valley, road building and irrigation technology came to Sichuan and the Hanzong Basin. The relics (some still in use) of these ancient engineering activities, of which one of the best known is the Dujiangyan irrigation system near Chengdu, show a knowledge of water management that still amazes today’s engineers. North of Hanzhong, where the Bao River leaves the mountains, the travellers had to climb to get to the Han Valley via stone steps up to Chickenhead Pass as the Bao valley mouth was blocked by the “Stone Gate”. But for some time in the Han period, the road passed the Stone Gate through what is possibly the first mountain tunnel called the “Stone Gate Tunnel”. This ancient engineering feat is now under the waters of the Stone Gate Dam, but before the dam was flooded in 1969, the Stele from the surrounds were cut and taken to the Hanzhong Museum where the 13 “Stone Gate Treasures” are preserved. A book by Robert Harrist on carved stone Stele called “The Landscape of Words” [R.5] provides the best English language description of these treasures. But it is now no longer possible to visit or pass through the tunnel.

Shu Roads historical- and eco-tourism

As a place where history, ancient and modern technology, environment, natural religion and conservation are co-located with adventurous trails through forests and mountains and along wild rivers, it is clear that the Shu Road region forms a very suitable destination for modern travellers. However, although the history and relics of the Hanzhong and Shu Road areas are well known to Chinese people they are not so well known among western people who would come looking for walking trails and experiences of wilderness. The author hopes this introduction to the region, its history and environment can be a useful contribution to changing this situation. As an example, Zibai (Purple Cedar) Mountain is near the Zhang Liang Temple and famous for its relics of ancient Daoism as well as its unique geology and environment. It is the home of the rare Musk Deer. A climb to the top, as shown in Figure 13 is not for the faint hearted. It is just one of hundreds of opportunities that exist in the region for walking and climbing.

|

|

|

Figure 13 The road to heaven is still hard as you climb Zibai Mountain near the Zhang Liang Temple in the Qinling Mountains. |

A “Shu Roads historical and eco-tourism route” has been emerging in China and includes in its scope the ancient and modern history and culture that have existed along the way. As a concept it does not currently have the same effect on people overseas as might the better known “Silk Road” or the more recently popular “Royal Inka Road”[14] etc. and work is still needed to change these perceptions. The idea is a large one as the Shu Road network stretches from Xi’an to Chengdu and has links to the ancient Silk road in the north and with the Chamadao (Tea-Horse route by which tea from Yunnan was exchanged for horses from Tibet) route in the south. It has specific sub-sections (such as the Lianyun road or the Chencang road) as well as branches and twigs from its main trunk routes reaching “leaves” consisting of the sites that people will wish to visit – when they know about them and can travel to them. Some of the sites are ideal for eco-tourism and also have an interesting history (such as Zibai Shan) and others are primarily historical sites, temples, tombs and relics but with added scenic views, wildlife and opportunities to hike on walking trails. With active promotion, the number of Chinese and overseas visitors who wish to travel the Shu Road Routes will no doubt increase to benefit the people who live there and open up a different area of China’s history and culture to people from all over the world.

|

|

|

Figure 14 : Memorial to the Shu Roads and the achievements of Ancient Times at a rest area on the new Xihan (Xi’an to Hanzhong) Tollway |

The people and environment of the Shu Road Network faced disaster when on May 12, 2008 the Longmen fault slipped. The aftermath of the Wenchuan earthquake revealed terrible losses of people, infrastructure and relics. The landscape of northern Sichuan has changed and disaster at levels previously only brought about by rebel armies (such as the Taiping in the Qing period or the rebel Yellow Tiger of the late Ming) occurred in some of the cities along the southern sections of the former Shu Roads. Minority Qiang and Tibetan people, who lived in remote mountain valleys, suffered greatly from the Wenchuan Earthquake. Since then, the Chinese government has invested heavily in reconstruction and given specific support to minority peoples. The provincial governments have also been steadily repairing the damage to temples and relics and developing new tourism infrastructure – such as history parks and walking trails, which go well beyond the extent of what was in place before May 2008.

It is therefore a good time for people interested in History and Adventure tourism to visit the areas formerly covered by the many Shu Roads, to experience the historical relics and help support the livelihoods of the people who live there. In this they will join the increasing numbers of Chinese who are visiting their ancient regions for its history and to experience its natural environment. Bringing travellers and tourists to the sites has certainly become easier and safer as just before the earthquake struck, the new Xihan Freeway had been opened to traffic linking Xi’an and Hanzhong. Since then, modern freeways from Chengdu have reached Hanzhong and the complete freeway between Xi’an and Chengdu has become a modern high speed “Shu Road” and very fast trains cross the Qinling without hardship. The “Plank Roads” of the former routes are now replaced by modern tunnels through mountains and flyovers across valleys. It is fitting that at the first rest stop out of Xi’an there is a memorial to the Shu Roads (Figure 14). In the future the Tollways and the very fast train network will provide unlimited and rapid access to the Shu Roads historical and eco-tourism region and new feeder roads will allow access to sites to a degree that has never before been available throughout the thousands of years of the Shu Roads history.

Conclusions

Mountains, rivers and lakes have been subjects of Chinese art and literature since ancient times. In the history of the Shu Roads terrain has also been the ruling factor and the rivers are the agents of change as well as communication. Ancient people learned how to navigate the great east-west divide of the Qinling, Ba and Micang mountains and the north-south passages of the Longmen mountains to travel and transport goods between the Wei River valley and the Sichuan plain. Throughout the dynasties that followed, the Shu roads have linked north and south China with the Hanzhong basin as a middle ground and haven from the hard crossings of dangerous mountain systems. The roads attracted a population of people servicing the traffic and travel as well as maintaining a hinterland of people dependent on the materials they supplied and the trade they could take out. The history of the area thorough which the roads passed has been as hard as the travel but throughout the history the heroism and high adventure of the events that took place have put the region into a place in Chinese culture and literature occupied by few others.

The Qinling Plank Roads to Shu today are not as “hard” as they were in the past. But it is only in recent times when China emerged as a modern nation with advanced technology that the mountain areas have become fully and safely accessible to modern tourists and travellers. The modern road building and communications that have occurred provide both another chapter for the complete discussion of Shu Roads as well as an urgent need to manage the history and archaeology of the ancient systems. Starting with the road building of the period of war against Japan, modern roads have, in many places, obliterated relics and in other places, due to the actions of agencies and individuals, have led to relics being preserved in museums or as photographs, copies and rubbings rather than the original materials. Balancing preservation and exploitation has always been difficult and it is no less an issue for the Shu Roads than it is for any other system of historical communication paths.

But because of the conjunction of human innovation that found ways to traverse the difficult sections and the spirit of the ancient and modern road builders which saw them extend the road system across the major mountain systems that surround Shu/Sichuan, the Shu roads have until recently been a relatively unknown but patiently waiting area where western travellers could experience the history, environment and culture of the “Shu Roads historical and eco-tourism route”. Terrible as the events of the Wenchuan earthquake were, the follow up development provides an opportunity for the region’s history, natural environment and culture to become known to international visitors, for them to be able to access the relic sites and also for them to help rebuild the livelihoods of the people who live along the routes of the ancient Shu Roads.

Acknowledgements

The Australia-China Council and the Shaanxi Relics Bureau have provided valuable financial support for the Shu Road project as well as organisation and publications from the Hanzhong “International Symposium on Historical Research of Plank Roads and Applications of 3S Technology” in 2007. This project and activity led to the development of this summary. The staff of the Hanzhong Museum and Director Feng Suiping, have made my personal “discovery” of the Plank and Shu roads a great adventure. The Google Earth image in Figure 4 was created using Google Earth Pro licensed from Google Inc.; Ruth Mostern, University of Merced, California USA provided the image for Figure 7. Figure 10 was provided by the kind permission of Frank Moore of Melbourne, Australia. Figure 2 is from the Historical Atlas of China by Herrmann (1966, [R.32]).

References

[R.0] Jupp, David, Brian Lees, Li Rui and Feng Suiping (2008). The Application of 3S Technology to Plank Road research and development of spatial information systems in the Qinling and Daba Mountains: I. Geographical, Geological and Historical Background; II. 3S Technology and the Australia-China Project. Collected Papers of the International Symposium on Historical Research of Plank Roads and Applications of 3S Technology, Shaanxi Peoples Education Press, Xi’an.

[R.1] Wiens, Herold J. (1949a). The Shu Tao or the Road to Szechuan: A study of the development and significance of Shensi-Szechuan road communication in West China. PhD Dissertation, Department of Geography, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

[R.2] Wiens, Herold J. (1949b). The Shu Tao or Road to Szechwan, Geographical Review, 39 No 4, pp. 584-604.

[R.3] Needham, J., Wang, L. & Lu G.D. (1971). Science and Civilisation in China. Volume 4. Physics and Physical Technology, Part III, Civil Engineering and Nautics.

Cambridge University Press.

[R.4] Justman, Hope (2007). Guide to Hiking China’s Old Road to Shu. iUniverse Inc., New York Lincoln Shanghai, 436p.

[R.5] Harrist, Robert E. (2008). The Landscape of Words. Stone inscriptions from early medieval China. University of Washington Press, 397p.

[R.6] Li, Zhiqin, Yan Shoucheng & Hu Ji (1986). Ancient records of the Shu Roads, Xi’an, Northwest University Press. (In Chinese).

蜀道話古,李之勤,阎守诚,胡戟 著,西安,西北大学出版社,1986

Shu dao hua gu, Li Zhiqin, Yan Shoucheng, Hu Ji zhu, Xi’an, Xibei Daxue Chubanshe, 1986

[R.7] Feng, Suiping (2003). The Northwest’s little South China – Hanzhong. Three Qin Press, Xi’an, Nov. 2003. (In Chinese).

小城春秋丛书: 西北小江南 -- 汉中,冯岁平 著, 三秦出版社,西安,2003

Xiaocheng Chunqiu Congshu: Xibei xiao Jiangnan -- Hanzhong, Feng Suiping Zhu, San Qin Chubanshe, Xi’an, 2003.

[R.8] Mostern, Ruth and Elijah Meeks (2008). The Qinling Frontier and the Construction of Empire in China: Three Examples from Early and Middle Period History. Collected Papers of the International Symposium on Historical Research of Plank Roads and Applications of 3S Technology, Shaanxi Peoples Education Press, Xi’an.

[R.9] Meng, Qingren, and Zhang, Guowei (2000). Geologic framework and tectonic evolution of the Qinling orogen, central China. Tectonophysics, 323(3-4), 183-196

[R.10] Sima Qian (120 BCE). Records of the Grand Historian. Translated by Burton Watson, Three Volumes (Revised 1993): Qin Dynasty, Han Dynasty I, Han Dynasty II. Columbia University Press.

[R.11] Twitchett, D. and Loewe, M. (Eds). (1986). The Cambridge History of China. Vol I, The Ch’in and Han Empires (221 B.C. – A.D. 220). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[R.12] Luo Guanzhong (fl. 1360). Three Kingdoms. (Novel: Sanguo Yanyi) Translated by Moss Roberts. Foreign Languages Press, Beijing, 1994.

[R.13] de Crespigny, R. (1984). Northern Frontier – The politics and Strategy of the Later Han Empire. Faculty of Asian studies, Australian National University, 1984.

[R.14] de Crespigny, R. (1991). The Three Kingdoms and Western Jin: A history of China in the Third Century. East Asian History, 1, 1-36; 2, 143-164.

[R.15] Minford, J. and Lau, J.S.M. (2000). Classical Chinese Literature. Volume I: From antiquity to the Tang Dynasty. The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Chinese University Press, Hong Kong.